|

ART stands for

"assisted reproductive technologies." I discovered this when my husband and

I confronted the hard fact of our secondary infertility. Perhaps it is because

I am an art historian that the invention of another referent for "art," already

so charged with meaning, captured my attention. The new usage, albeit peculiar

to the medical profession, seems as much an extension as a jarring displacement

of the word's conventional semantic range. Whether originally intended to do

so or not, ART puns on notions of creativity and skill, ingenuity and artifice

through which we humans act upon and transform the "found" order of things in

the everyday world. The acronym cleverly plays on the tension between the colloquially

opposed categories "art" and "science." Closely related terms in Latin for describing

knowledge, ars and scientia have come to represent antithetical

branches of learning or fields of endeavor. Self-consciously or unconsciously,

ART positions the practice of medicine somewhere in-between, unmasking the pretensions

of ars medicae, the healing arts, to science or, vice versa, masking

the aspirations of scientific control to art. The age-old debate over the artist's

proper task could just as well be applied to the physician: improve on or compete

with nature, respect or challenge it?; find harmony with nature or bend "her"

to "man's" will?

Artists and the coterie of specialists who govern

art's institutions, like physicians and ethicists, exploit and advance reproductive

technologies on which they seek, at the same time, to impose limits. Old master

and impressionist paintings are copied in the medium of ceramic tile for a Japanese

art collection; motifs from Edo screens and Ming Dynasty scrolls unfurl on fancy

scarves in museum boutiques; details of altarpieces surface on Christmas cards,

miniatures from illuminated manuscripts in date-books. The digital imaging processes

of the Cyberspace Age turn all objects virtually into a genre of clip-art. As

numerous commentators have observed countless times, reproduction begs questions

of authenticity, place-value and ultimately ownership. Images, excerpted like

genetic material from more complex entities, give life to the consumer products

by which we measure the success of our seasons. Extracted, interjected, transferred,

reconfigured as so many different identities...exactly what in "art" belongs

to whom?

Armand and I had easily conceived our son Ira,

born in August 1990, but our concerted attempts to conceive again proved unsuccessful.

By early 1994 we had embarked on a course of medical treatment that included

cycle after cycle of intra-uterine insemination (IUI) and then of in-vitro fertilization

(IVF). After years in which art had constituted my object, my body became an

object of ART. I "worked on" medieval churches and their paintings. Now I was

worked on - probed, analyzed, interpreted. Once, I did achieve pregnancy, only

to suffer a miscarriage at ten weeks. My response to this blow was to persist

with yet another annual round of expensive, high-tech interventions, each of

which failed. The more I tried, the greater my exasperation and sense of defeat.

I knew, as I turned forty-one, that my prospects for becoming pregnant were

dwindling (in direct proportion to our savings). Slowly, and with great reluctance,

I began to give my body permission to claim victory. ART, in my case at least,

could not prevail against the power of nature. Yet under no circumstances did

my evolving acceptance of the inability to conceive mean acquiescence: on the

subject of another baby for our family, biology was not going to have the last

word.

What makes my story worth telling is not some

uncanny insight I have gleaned from a painful journey. Its tropes of willful,

almost obsessive, determination and profound despair are all too familiar to

women who have suffered infertility. Rather, I undertake this risky literary

venture on account of the form in which my self-reflection takes shape. Fragments

of recollected experience crystallize in terms of images that I have encountered

in my research as an historian of medieval art. Images from the distant past

are so deeply burrowed into the recesses of my consciousness that, fantastically

transfigured, they sometimes invade my dreams. There, in sleep, I marvel, the

amazed spectator of wondrous new artworks from a world long since vanished.

While historians today examine how being embedded in a particular cultural moment

may color their own (or their predecessors') interpretation of the past, I find

myself performing the inverse operation. Thus study of the Middle Ages, spilling

over into the disparate arenas of my life, becomes a prism through which I revisit

my infertility. The writing of history weaves the life and times of others into

art. Turning my practice as a historian to my own life, I offer the following

bricolage of iconography, anecdote and critique.

The

Cult of the Clinics

|

Fig.

1.

From the window

of her cell, Saint Radegund expels a demon from the possessed woman Leubile,

miniature painted c. 1100, Poitiers, Bibliotheque municipale, MS. 250 (Life

of Saint Radegund), fol. 35r.

|

Fig.

2.

Saint

Radegund cures Bella, from the same manuscript, fol. 34r.

|

My

first encounter with ART occurred in June 1993 on a trip to Norfolk, Virginia

where I had an early morning appointment to examine twelfth-century sculpture

in the collection of the Chrysler Museum. I spent the night at a pleasant Bed

and Breakfast near the museum. The next day, I met two women conversing over

coffee and blueberry muffins. With the same blase nonchalance one might remark

on the local weather, they were comparing their husbands' sperm counts. They

had traveled here from Istanbul in order to undergo IVF at a well-known clinic

also within walking distance from the B & B. Their husbands, having completed

that part of the protocol for which their presence was necessary, had just returned

home (they had important jobs). Another cup of decaf, more vital statistics:

how many follicles their ovaries had produced, how many eggs retrieved, how

many fertilized, how many times the embryos had divided so far, their grades.

Both women were anxiously awaiting embryo transfers: how many would be put back

in the womb, how many frozen for later use? The proprietor-hostess replenished

the tray of muffins...she knew the routines. What planet had I landed on? But

it was not so much the unfamiliar talk or its incongruous setting that disturbed

me as the eery feeling of its personal relevance.

At once unsettled and intrigued, I began to ask

questions. Armand and I were having unexpected difficulty conceiving a second

child. Testing indicated a "male factor," I confided. Armand's urologist suggested

that the problem could easily be corrected by a minor surgical procedure. We

would then have to wait about three months to see whether motility and count

would improve. Don't bank on it, my breakfast company warned; the same procedure

had been performed on their husbands but turned out to have little or no impact

on sperm quality. So I listened intently as each woman described her couple's

medical history, their infertility work-up, their daily regimen of injections,

ultrasounds and blood-levels, the number of attempts at IVF in Norfolk and elsewhere.

The price-tag? Approximately $10,000 per trial - not including fertility drugs

(add some $2,000) or lab "extras" like the micro-manipulation required to inject

a single sperm directly into an egg (intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection, or ICSI,

another $3,000). I began to feel slightly nauseous and left for the museum,

my head spinning. Although I had come to Norfolk to look at miscellaneous stone

carvings scavenged from the distant past, I now stared aghast at my future.

Several months later, under pressure of my thirty-ninth

birthday and disheartened by the predictable failure of the surgery, Armand

and I decided to advance a notch in the hierarchy of resort. Well-meaning urologists

and gynecologists were competent in their own respective spheres but I needed

advice of a higher order; most of all, I wanted results. We then did what people

seeking relief from physical ills have done since time out of mind. Leaving

behind the village soothsayer and empiric, we heeded the irresistible call of

the pilgrimage roads and made our way towards the shrines that reported the

greatest numbers of miracles.

Where would we find the mightiest wonder-workers?

Fortunately, shrine clergy carefully tracked the successes of their resident

luminaries. Saints not performing to standard, not maintaining respectable quotas

of cures and punitive strikes, would eventually lose their luster. They could

be humiliated, their bones dumped unceremoniously onto the sanctuary pavement.

Should they still refuse to come to their senses, they might even be abandoned

by their custodians. Saints had to keep up, or face obsolescence. Inventio,

the ritual finding of new relics, kept old patrons in line, motivating them

to tackle each scourge and every bout of pestilence. Competition has historically

proved a powerful incentive. If saints put out for their sanctuaries, surely

ART doctors would do the same for theirs. I had faith in the system. Armand

and I completed the requisite battery of diagnostic tests at the end of 1993

and began treatment in early 1994 at a clinic in the Washington D.C. area where

we lived. The slight variation in pregnancy rates elsewhere did not seem to

justify the considerably greater expense of travel and disruption to our daily

life. In the end, pragmatic constraints make most pilgrimage (like politics)

a local affair.

Since male factor infertility in our case had

an unknown etiology and since Armand had in fact fathered our son four years

before, we decided to try a few IUI cycles on the off-chance that perhaps sperm

quality had not really changed all that much in the intervening period. While

pursuing this low-tech procedure, I would boost my fertility with the cheap,

easy-to-take pill, Clomid. Perhaps we might "get away" with this less aggressive,

more economical approach. A few thousand dollars later, however, we graduated

in June 1994 to IVF with ICSI. The fears stirred in Norfolk the previous June

had come to pass.

At the time of my experience with ART, IVF had

a success rate of around twenty percent under the very best circumstances. Couples

in which the female was well under thirty-five and had good ovarian function

and the male, punchy sperm might have a decent shot at a baby through IVF or

one its variants. The more eggs harvested and fertilized, the more embryos developed,

the greater the chance of achieving a pregnancy (eventually). The particulars

of our secondary infertility, however, made for a grim prognosis. Two obstacles

combined to present an intractable case: the fact that I was approaching forty

handicapped the treatment of male infertility. Women in my age group could expect

to produce fewer eggs under ovarian stimulation, not all of optimum quality.

Then, in order to maximize fertilization, the retrieved eggs would be subjected

to the technique of ICSI. Probably not all the eggs would be fertilized and,

of those fertilized, not all would necessarily progress further into multi-cell

embryos. But the real blind-spot in the IVF process followed embryo transfer.

What fostered or impeded implantation was anyone's guess.

Taking into account these variables, IVF increased

our chances of achieving pregnancy from zero to around sixteen percent. The

chance, however, of actually having a live birth decreased to around thirteen

percent, since miscarriage (as in natural conception in my age group) remained

a possibility. According to my rough calculations, Armand and I had at least

as much chance of a successful outcome as did the infirm who congregated around

the tombs of medieval saints. If anything, holy bodies reposing in their reliquaries

had a better clinical record. ART indeed improved the hand that nature had dealt

to some couples, but the desired result, a baby, was still a distant prospect.

Yet we desperately hoped for a miracle. Every other couple I met on the fertility

circuit prayed that they, too, might rank amongst the chosen on the right side

of the statistical curve. There were no unbelievers.

The negative pregnancy test, accompanied by the

very negative balance on our bank statement, jolted me back to the late twentieth

century. "Now what?," I asked the medical director of the clinic, fighting back

tears.

Unsurprisingly, he recommended a second attempt;

we should look at the first cycle as a trial run.

"But it's so expensive, basically we'd be gambling

away another $15,000."

"You know," he replied, "children are an enormous

financial responsibility; maybe you can't afford a second one."

Taken aback by the doctor's caustic remark, I

pretended not to register its weird logic. Instead, I pursued a rather different

line of inquiry. "Since the main impediment in our case is sperm quality, what

if we tried IUI cycles using donor sperm?" Indeed, the clinic's specialist in

male infertility had from the start proposed both this method and adoption as

alternatives to IVF. "Wouldn't I have a better shot at becoming pregnant than

by repeating IVF?" I persisted.

"Yes," he brushed me off. Little did I know then

that to refuse the newly invented remedy for male infertility was tantamount

to heresy.

The

Wheel of Urines

|

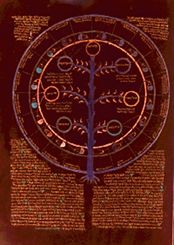

Fig.

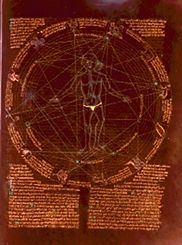

3.

Wheel of Urines,

miniature painted c. 1420, London, Wellcome Institute Library, MS. 49 (Wellcome

Apocalypse), fol. 42r.

|

My

birthday came and went, forty years too quickly spent. Forty is a magic number.

The Judeo-Christian tradition appoints it the ultimate figure of liminality,

a term anthropologists use to describe the transitional phase in rites of passage.

Before attaining a new status within the community, an initiate undergoes a

dynamic process of change during which he or she is set socially apart and often

remains physically confined to a discrete sphere of existence. This interim

stage of separation, which follows exclusion or withdrawal from society and

precedes re-integration on different terms, may be fraught with uncertainty,

even danger. The interval between conception and birth, forty weeks, yields

the archetypal measure of suspended transformation; the developing fetus embodies

the ambiguous state of abeyance between non-being and full identity.

God caused it to rain upon the earth forty days

and nights, cleansing "his" creation of every breathing thing outside Noah's

ark. Over time the flood waters subsided and finally, "...on the first day of

the tenth month, the mountain peaks appeared. At the end of forty days Noah

opened the porthole he had made in the ark...(Gen. 8:5-6)." [After nine months,

the womb opened and a new world came forth, head first.] The Hebrews wandered

for forty years in the desert until a generation that had never known slavery

crossed into the promised land, a people reborn. Jesus fasted in the wilderness

for forty days before assuming his ministry. The Levitical injunctions (12:1-5)

designate the period of a woman's postpartum purification as forty or eighty

days depending on whether the infant is male or female.

Along the continuum of a woman's reproductive

life, forty is the age that ART specialists have designated as the benchmark

in the inexorable decline of natural fertility. A single point thus stands for

the transitional years in which the mature female body, no longer in its prime

but not yet depleted, marks time before finally reaching menopause. Why forty

rather than thirty-eight or thirty-nine? An arbitrary cut-off based on science,

or on the convenience of a figure now so culturally diffuse that its ancient

symbolic charge goes unnoticed?

Magic has its uses. When my biological clock sounded

its alarm, a way opened in the marital union for recourse to donor sperm. Unorthodox

though it was, Armand and I decided to proceed by technologically reversing

course. We returned to Clomid and artificial insemination but now enlisted the

assistance of a few surrogate cells picked out from a list of numbers. It was

a difficult and emotionally wrenching choice for us both. The sense that we

were somehow going against the professional grain only made it more stressful.

During one procedure, a nurse held up the vial of sperm, read the number on

the label and asked,"Is this the man we want?" I responded that I did not regard

the bodily fluid in the tube as a man. Odd, I thought. Although the practitioner

was accustomed to dissociating genetic material from the women who donate eggs

or provide surrogate wombs, she glibly conflated sperm with the male person

who was its source. Yet her words spoke nonetheless pointedly to my residual

feelings of guilt. Had insemination with donor sperm demoted me to a less-than-faithful

wife? I felt ashamed.

Five cycles brought us to mid-January 1995. Meanwhile,

on January 1, our medical insurance policy changed. We had switched health plans

so as to take maximum advantage of a new Maryland law. The state that underwrote

Armand's employee benefits now mandated full insurance coverage of three IVF

attempts per couple per lifetime. If the IUI cycles proved unsuccessful, we

would have the option of trying IVF at a different clinic, one which our managed

care provider authorized. True, our insurance would not cover injectable fertility

drugs or the then still "experimental" technique of ICSI. But at out-of-pocket

costs of "only" $5,000 per trial, as opposed to $15,000, IVF seemed like a bargain.

Soon after the last IUI, we went for our first

consultation at the pre-approved clinic, associated with a major hospital in

downtown D.C. Since the hospital pharmacy had a limited stock of the fertility

drug Pergonal, in high demand and short supply everywhere, we purchased a few

boxes in the event we decided to "cycle." (In conversational ART-speak, "cycle"

is a verb as well as a noun, just as ICSI is both a verb and an adjective, as

in "to ICSI" the eggs, or "ICSIed" eggs). Two weeks later, however, I found

myself going to the clinic not for IVF but, with no menstrual period in sight,

for a pregnancy test. It turned out positive. At last! Relieved and thrilled,

I returned the unopened boxes of Pergonal.

The weekly count-down to which I had so long looked

forward had begun. Forty, thirty-nine, thirty-eight... thirty-four...ultrasound

at the clinic...thirty-two, first OB appointment, thirty, twenty-nine... And

then, late one Saturday afternoon, blood everywhere, dreams awash in an unmerciful

gush of bright red waste. When the emergency room staff confirmed the miscarriage,

Armand wept. The absence of his genes in the fetus I carried had in no way diminished

his profound sense of loss. Numb with grief, I continued to count the weeks.

How many would it take for my body to heal so that I could resume my place on

the fertility treadmill?

June 1995. Two years after my initial contact

with ART at Norfolk and we were still at ground zero. I had proved I could become

pregnant with IUI and donor sperm. Should we return to this method or go forward

with IVF? The physician on whom we now relied persuaded me (skeptical though

I was) that my age warranted the most aggressive approach possible. I had, after

all, crossed the threshold into the over-forty category. In any case, I had

taken Clomid many more times than he believed was advisable (a risk of cancer

increased with sustained use). As long as I would have to take injectable fertility

drugs like Pergonal or Metrodin, why not do an IVF cycle for which we had the

insurance coverage? To ICSI or not to ICSI? That was my question. He adamantly

and persuasively argued that our best chances for fertilization lay in using

the ICSI technique with Armand's sperm, rather than in combining my eggs with

donor sperm in a "natural" IVF cycle.

The start date of an ART cycle is closely correlated

with the onset of the menstrual period. My short-lived pregnancy had ended with

an unwanted flow of blood. Now the regular monthly event I dreaded most was

the signal I eagerly awaited. I kept watch for the red flag that meant I could

now try again. Maybe this time we would get lucky. The fertility circuit converts

endings into new beginnings, a source of comfort and, at least for me, a compelling

force for repetition.

At the appropriate point in the cycle, Armand

began twice daily to give me intramuscular injections in the hip. There was

evening and there was morning, the first day of many in which a powerful fertility

drug surged in my veins. The pharmaceutical contained reproductive hormones

that control the ovaries (organs also called gonads) so as to stimulate the

growth of the follicles, or cellular pockets, in which the eggs develop. These

hormones were extracted and purified from the urine of post-menopausal women,

who happen to secrete high amounts of natural gonadotropins. During the era

of my involvement in IVF, the necessary hormones were not yet manufactured synthetically

through recombinant DNA technology. Urine was the only source for the industrial

production of human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG) preparations like Pergonal

or Metrodin. Clearly the historical preoccupation with urine, the medieval physician's

main diagnostic tool, had paid off.

ART, it thus turns out, is a recycling program.

Hormones recovered from the excreta of older women enhance the fecundity of

younger women. When a girl becomes nubile she bleeds from her vulva, and when

menstruation ceases the by-products of her former capacity for reproduction

are expelled through the same orifice. From blood to urine, and with injections

of hMG, back to blood. As medieval people had known all along, female effluvia

are life-giving substances. Women supply the blood, the very matter, from which

they first concoct the fetus in their oven-wombs and then the breast milk, twice-cooked,

for nursing the baby after birth. Even the superfluous blood released in menstruation

can play an important role in procreation. Beatrice de Planissoles, a noblewoman

who lived during the late thirteenth- and early fourteenth century in the southern

French village of Montaillou, took special precautions to ensure the viability

of her daughter's marriage. She kept cloth that had been soaked with the girl's

first menstrual blood, a precious elixir, so that one day she might remove some

to mix into the drink of her son-in-law, thereby guaranteeing his marital fidelity.

I doubt Beatrice would be surprised to learn that ingredients distilled from

her own urine might prove useful in the generation of her grandchildren.

Especially interesting to me, however, is the

purported role of nuns in the manufacture of Pergonal, the oldest hMG preparation

on the market. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Instituto Farmacologico

Serono in Rome (a subsidiary of the Swiss pharmaceutical firm Ares-Serono) obtained

eighty thousand liters of urine from post-menopausal nuns and other women in

rural Italian communities for the extraction of reproductive hormones. Why the

selection of cloistered women as "naturally" the most suitable or expedient

source of urine? And what lies behind their donation to Serono: a love of science,

an exchange of gifts? The nuns' contribution to the production of a highly purified

fertility drug, however ironic, makes perfect sense to a historian of medieval

culture. The more radically that holy women of the thirteenth and fourteenth

centuries sealed off their bodily cavities, the more miraculous their bodily

exudings. The sweat and saliva of starving virgins cured infirmities, and their

divinely induced lactation provided sustenance. Surely it seems only a matter

of time before a pharmaceutical company tapped into convents for urine from

female bodies practiced in renunciation and transformed by charity. Who else

but older women vowed to chastity could possibly eliminate waste that might

heal the infertility of younger women? The Serono program merely extended a

deeply ingrained tradition of spirituality, not to mention ancient principles

of sympathetic magic, in a new direction. Did technology reactivate a cultural

memory, long dormant perhaps, but never totally eradicated?

Bloodletting

|

Fig.

4.

A barber surgeon

bleeds a woman, woodcut in I-Eeronymus Brunschwig, Liber pestilentialis de venenis

epidimie. Das Buch der Vergifit der Pestilentz, printed by Johann (Reinhard)

Gruninger, Strasbourg, 1500, fol. XXVv.

|

In

giving over my body to ART I became a member of an order, the demanding protocols

of IVF a rule that set me apart from the work-a-day world of ordinary folk.

I opened my Book of Hours at 5:30 a.m. with the meticulous ritual of injection.

First Armand and I had to mix the precise amount Pergonal or Metrodin powder

with sterile solution. I snapped open the glass ampules containing each substance.

Armand did the needlework, drawing up the solution into a syringe, infusing

it into a vial of powder, again drawing up the now dissolved medicine, infusing

the liquid into several more amps of powder. Armand replaced the thick mixing

needle with a long, thin and equally terrifying one. While he removed residual

air bubbles by flicking the side of the syringe, I pointed to a spot just slightly

to the back of my hip. Armand aimed and lunged. I gritted my teeth against the

pain that began my day.

By 6:00 a.m. I was out the door, headed towards

the metro and the clinic for monitoring. At 6:45 the waiting room was already

crowded with women. Each of us wondered in silence about the follicles proliferating

in our ovaries. No chatty coffee klotch and no blueberry muffins here. The ultrasound

technician brought the shadowy image of my ovaries onto the screen and I waited

with baited breath as she counted and measured the bulbous black blobs, each

of which potentially concealed an egg. The more follicles, the more eggs, the

better our chances... Then on to the lab technician for "blood work" so that

hormone levels could be ascertained. Another line to attend. Which technician

would draw my blood today? Some were so adept that I hardly felt the needle,

others so heavy-handed that thirty seconds seemed an eternity. Back on the metro.

When I finally sat down to my work around 9:00, I was exhausted. Between 3:00

and 5:00 p.m. I waited for the nurse to phone with instructions based on the

physician's review of the data. 6:00 p.m., vespers: Armand and I repeated the

injection ritual, thus concluding the office of IVF for the day. So we continued

until, in the fullness of time, the follicles abounded and grew fat and my blood

was saturated with the stuff of their ripening.

Finally the evening came for Armand to inject

me with a different pharmaceutical preparation. It contained human chorionic

gonadotropin (hCG), the hormone secreted by the placenta during pregnancy. Bringing

the eggs inside the follicles to maturity, the hCG would trigger ovulation twelve

hours later. The scheduling of the injection therefore had to be precisely coordinated

with the next phase of the IVF cycle, egg retrieval. Using an ultrasound-guided

needle, the physician had to aspirate the eggs just before the follicles naturally

ruptured, or the eggs would be released and "lost," the cycle ruined. Time was

of the essence.

Now "our" clinic was associated with a hospital,

and egg retrievals were performed - of all places - in the maternity ward. The

elevator doors opened to a view of the nursery full of beautiful newborns. Was

this supposed to be inspiring? No, convenience and efficiency dictated the set

up: women in labor and women in the IVF program could to some extent share the

same medical equipment and staff. The juxtaposition of the "coulds" and the

"could nots," however, always struck me as more than a little cruel. True, successful

ART patients might find themselves returning here in nine months but the vast

majority of us would never make it to the delivery room. Indeed, by the time

I got to this point in my second IVF cycle, after having miscarried some eight

weeks earlier, I could not even bear the sight of pregnant women. The longing,

the frustration, and oh yes the envy were just too overwhelming. I had to avert

my eyes from bellies and babies; had to shut the openings through which I felt

most vulnerable and, like female saints of yore, close myself in to gain some

semblance of control over my life.

Armand and I were led into one of the birthing

rooms where the anesthesiologist administered an epidural. Five years before

I had an epidural during labor with our son. Now I belonged to the other group,

from whom nature withheld the fruit of the womb. I was wheeled into a room down

the hall. My doctor and his assistants were ready for the routine procedure,

the technicians in place in the adjoining IVF laboratory ready to receive the

eggs. Then the unthinkable happened. A woman in labor with twins was rushed

into the adjacent delivery room; the obstetrical staff needed the one and

only ultrasound machine on the floor. We would just have to wait. The eggs

in which I invested my shattered hopes for another chance at pregnancy might

be lost. My doctor, clearly irritated by the predicament in which we found ourselves,

was as helpless as I was motionless.

"You do understand, don't you, that in there it's

a matter of live babies," he reasoned. "These, well, are just eggs."

"Doctor," I managed to reply, "this is a big hospital.

Isn't there somewhere another ultrasound machine we could use."

"No. Not one of the right sort."

"I hate to bring this up, but" [given the hefty

fees patients and some insurance companies shell out for IVF - a thought I kept

to myself] "don't you think you might buy another machine... I mean, couldn't

there be two ultrasound machines..."

"Well maybe now. This never happened before."

I listened, intent upon the sounds coming through

the door that connected the IVF procedure and delivery rooms. Voices were coaching,

she was pushing and screaming and pushing and screaming. At last, applause accompanied

a baby's cries. The ultrasound machine, no longer needed since the second baby

was on its way, was freed for our use. Twenty minutes to the twelfth hour. The

team worked fast. The follicles were intact; the eggs were still there! The

harvest went forward. Meanwhile, in the next room, the second baby was born

to another round of applause. Drifting into the nether regions of my darkest

despair, I knew in a flash the utter futility of all my extraordinary efforts

at pregnancy.

"Why those tears?" one of the nurses asked me.

"You just got six eggs."

The specialist in ICSI went to work on my eggs

and Armand's sperm. In twenty-four hours we would hear from the IVF coordinator

about fertilization and thereafter about embryo transfer. Two days after the

retrieval, Armand and I returned to the maternity ward for phase three of the

cycle. A nurse, freshening up one of the birthing rooms just vacated, carried

out congratulatory balloons and flowers. Not for us; we had three embryos. At

least this time I would not have to compete for an ultrasound machine, as the

transfer required none. We were all in a lighter mood. As the embryos were pipelined

into my uterus the doctor joked about his recollections of the art history course

he had taken from the legendary professor Horste W. Janson, whom I knew only

through the famously lucrative textbook he had authored. I had to refrain from

laughing in the hope that the embryos would settle into the plush uterine lining

prepared to receive them. Finishing touches on a work of performance ART, the

collective enterprise of anonymous master craftsmen in the lab and of countless

invisible women whose secretions made possible my own. A postmodern story familiar

to every medievalist.

Two weeks later, I went back to the lab for a

blood test that would determine whether or not implantation had occurred. Positive

for pregnancy or negative? The six excruciating hours I waited by the phone

for the results capped an excruciating fourteen days of wondering if the embryos

were still there, of imagining cell division, of hoping... Finally the phone

rang. "I'm very sorry," the IVF coordinator apologized, "it's negative. Stop

taking the progesterone and you'll get your period within a couple of days.

The doctor will call you and you can come in for a post-cycle consult." Why

hadn't those embryos implanted? Maybe this or that movement in the recovery

room had disturbed them; maybe I shifted my position too much in the first twenty-four

hours; maybe I doubted too much. Maybe if I had a more positive attitude...

I momentarily buried my sorrow in order to pick up Ira from his pre-kindergarten

class. Tearing out the school door into the June sun, he rescued me from the

crowd of all those moms pregnant two and three times over. I would not be one

of them.

From blood to urine and back to blood. Thousands

of dollars' worth down the sewer, I thought, as I flushed the toilet. Women's

monthly bleeding is a calendrical system, an involuntary periodic flow that

keeps time in accordance with the moon. No wonder, then, that the voluntary

letting of blood to restore humoral equilibrium was aligned with heavenly bodies

whose movement divided day from night and one month from another. Zodiac Man

may claim to represent a universal medical standard for the practice of phlebotomy.

In fact, however, his is but a mirror image of the power that Nature vested

in the rhythms of female bleeding. How to appropriate the power of woman's fertility

is a matter for Culture to answer. Gazing into the sky, I could only rail against

my fate. I was locked in a cosmic struggle. And I was losing.

Why did the IVF cycle fail? The postmortem conference

with our doctor provided no information. What else was there to do but repeat

the procedure; we had coverage for two more attempts. We looked at the calendar

trying to predict when my next period would begin so as to get a sense of when

we might cycle again. We would then make our summer plans. During my two years

in ART I had grown accustomed to scheduling my professional activities and family

vacations around my menstrual periods, count-down for all fertility therapy.

My body may have held me captive to its reproductive tides, but I was a willing

and docile hostage. At our clinic, two physicians performed IVF on an alternating

basis: each cycled his patients every other month. In July our doctor would

not be available. We made the calculations accordingly.

The success or failure of our late August/ September

cycle was determined, as it turned out, on the first day of Rosh HaShannah,

the Jewish New Year. What a coincidence. On the birthday of (Adam's) Creation,

we in synagogues everywhere recall three barren women of the Bible: Sarah, Rachel

and especially Hannah (1 Samuel 1-2:11), whose prayer sets forth the holiday's

central themes. God remembered them and they conceived. Infertility overcome

is the founding story of the Days of Awe, which open the harvest season at the

head of the agricultural year. Divine judgment looms over the process of reaping

what one has sowed, an annual reckoning that takes as its sign the mastery of

women's bleeding. We attended a service for young children with our son. The

rabbi initiated a collective celebration of congregants' various accomplishments.

"Families that had a new baby in the past year, come up to the bima (pulpit),"

she called out. Peninnah's piercing words. From the depths of bitterness and

resentment, I poured out my grieving soul. What would be the results of the

blood test I had taken early that morning? In the late afternoon, the IVF coordinator

phoned, "I'm sorry, Marcia, it's negative." My bleeding was not to end.

Some days later, I turned forty-two. "But," said

the mother of Ira's kindergarten friend as we walked home from the local elementary

school, "you look really young; I thought you were in your early thirties."

"Tell that to my ovaries," I cracked. We had insurance coverage for one last

cycle, which we completed to no avail in November/ December. By the end of 1995,

we had been bled dry. Emotionally and physically drained, I had reduced my life

to follicles projected on a screen.

The

Kindness of Strangers

|

© British

Library - further reproduction prohibited

Fig.

6.

An infant, swaddled

and abandoned at a city gate, historiated initial, c. 1360-75, London, British

Library, MS. Royal 6E VII (Omne bonum Encyclopedia), fol. 104.

|

During

the five months in which Armand and I organized our lives around our last two

attempts at IVF, we also began seriously to explore adoption as a way to build

our family. I began to ask myself what it was I really wanted, to become pregnant

at all cost or to have a live baby? I began to decouple the two goals,

for it slowly dawned on me that if I endlessly pursued the first, the second

might well go unrealized. To let go of trying to conceive would be tough;1

not to cradle

another baby of my own would be unbearable. Our resources were finite and we

were not getting any younger. I might ultimately have to choose between chasing

a desire to give birth a second time and looking beyond to the fulfilment that,

I knew for me, lay in a lifelong bond between parent and child.

The "dead time" between cycles, built into the

alternating schedule of the physicians in the IVF program at the clinic, allowed

me to prepare the ground for adoption. Individually and as a couple, Armand

and I examined our feelings. Would adoption be right for us? We took a series

of seminars sponsored by FACE (Families Adopting Children Everywhere). I researched

and gathered information. We networked through our many friends, neighbors,

colleagues and relatives who had adopted their children. We did not shirk from

asking ourselves and others hard questions. Investigation of the pragmatic aspects

of adoption and personal reflection on the issues that adoption would raise

in the specific context of our family blended together in an integral learning

process.

We attended "open houses" offered on a regular

basis by many adoption agencies in the Washington Metropolitan area. I compared

the business of ART, a purely capitalistic venture, to the adoption industry,

subject to more government regulation but market-driven nonetheless. Strangely

(or perhaps not), the medical and legal solutions available to infertile couples

seemed keyed into a common index of value, as if professionals in both fields

shared pricing guidelines and mutually adjusted their fees. How else could IVF

and adoption, involving radically dissimilar operations and expertise, so consistently

parallel one another in their cost to the consumer? Clearly the commensurability

of the two services depended, in the final analysis, on the product that we

dreamed they would deliver.

If fertility clinics tended to sell themselves

by pitching statistics in too free-wheeling a manner, agency presentations could

also be problematic. Often, as the highlight of such evenings, newly adoptive

couples displayed their babies and toddlers. Innocently intended to encourage

prospective couples ("yes, there is a baby at the end of the tunnel"), the practice

seemed unnecessarily exploitative. What were we desperate folk supposed to feel?

To what position did the showroom scenario reduce us? Were we shopping? Was

this supposed to assure us that yes, our children too would be healthy and free

of defects? Why did "special needs" cases, if they came up at all, get swept

under the rug, a trivial concern, a rare occurrence?

We could not escape the opportunism to which the

"free-enterprise" treatment of infertility in the United States is prone. Yet,

by the same token, I had to admit that I favored the flexibility which came

with it. We in America could take advantage of more options than allowed, say,

to our European counterparts, who face nearly insurmountable obstacles should

they wish to adopt. ART may indeed be more cheaply available in Europe, historically

obsessed with bloodlines. But should ART fail, tortuous bureaucracies make domestic

adoption practically impossible, where it is not altogether illegal, and immigration

laws, xenophobic in the extreme, severely restrict international adoption.

Armand and I decided on an international adoption,

preferably from China. Collecting the requisite original documents for notarization,

certification and authentication at the county, state and national levels proved

laborious. We needed official papers in French and English from three countries

(Belgium, where Armand was born and raised; Canada, where I happened to be born;

the U.S. where we lived), two states (New York, Maryland), one colony (the District

of Columbia), and God knows how many counties (Westchester, Montgomery, Anne

Arundel, Prince George's etc.). We built a comfortable working relationship

with a small agency in D.C. that respected our wish for as young an infant as

possible and agreed to advocate in China on behalf of our interests. I had originally

considered a larger, better-known agency based in another state, but had been

put off by the director who regarded adoption as an exercise in charity. Confusing

the strict, administrative process in Beijing with God's Will, he expected prospective

couples to accept selflessly and without question whatever awaited them.

He was not alone. Far too many adoption providers,

I discovered, tacitly assume that infertile couples (not unlike lepers in the

twelfth and thirteenth centuries) must be prepared to heed a divine calling

for which their misfortune sets them apart. I did not have a vocation for perpetual

penance, however. Adoption surely ought not be construed as a week-end excursion

to the mall; does that mean infertile couples should be targeted as a venue

for would-be do-gooders? Adoption entails choices - whether or not, for example,

to assume the responsibility of parenting a child with special needs - that

do not arise in giving birth, which presents a fait accompli. Such decisions

belonged to Armand and me, not God. As a patient in the fertility clinic, I

followed protocols to the letter. As a client of an adoption agency, I wanted

to call the shots. Taking an assertive stance felt wonderful.

Best of all, by turning my mind away from my ovaries,

I gave my heart a chance to open and grow. Something was stirring. Had a seed

been planted there? I felt an excitement, enthusiasm, and optimism I never did

during IVF. To accept and trust these feelings was another matter however. My

full and unwavering commitment to adoption evolved only gradually, in fits and

starts, over the course of many months. While completing the legwork for an

international adoption, we concurrently proceeded with the remaining IVF cycles

for which we had insurance coverage. My strategy, unconventional it is true

(and to some adoption agencies unacceptable), was to play one path against the

other in the belief that I could use the tension between the two to my advantage.

Thus I went forward with IVF no longer dreading that, for all the years of hoping

and yearning, I would come out with nothing; my life did not depend on a positive

pregnancy test. By the same token, I contemplated adoption without losing sight

of the authenticity of my own feelings and the integrity of my own needs; I

refused to let the religious or humanitarian agenda of others dictate my course

of action.

On the dreary December afternoon that we learned

the negative outcome of our last attempt at IVF, Armand and I (longstanding

afficionados of Chinese cinema) went to see the recently released film of Zhang

Yimou. I had nearly finished processing all the requisite documents and had

received our INS clearance. We resolved to take care of the outstanding details

by the end of the year. A couple of days later I spoke by telephone with an

old friend. I filled her in on the failure of the last cycle.

"We're moving ahead with our plans to adopt a

baby girl from China. I hope we'll have an assignment sometime in the spring

or summer."

"You can't be serious about going through with

this! Why can't you accept things the way they are? You have a son, he's five

and a half. Time moves on and you're going backwards. It would be different

if you got pregnant..." Her reaction took me by surprise.

"If ART had worked, and I had become pregnant,

you would be happy for me. So I'm not sure I understand...why is it okay for

me to have a baby naturally (of course, my sense of "natural" in matters of

procreation had long ago exploded) but not through adoption, which would be

to "go backwards?" What would be different if I got pregnant? Well I am not

going to get pregnant; for whatever reason, I just can't conceive. Can't I resist

the finality of biology? Did my only recourse lay in ART?"

My friend's incomprehensible position and lack

of support awakened my fighting spirit. I kept replaying the conversation in

my mind until I suddenly became aware of resounding questions that, strange

as it may seem, I had never consciously articulated, let alone attempted to

ponder. Why in fact had I been so invested in becoming pregnant? What was at

stake for me? What does pregnancy mean in our culture? Why is biological motherhood

valued above all? The critical act of framing my personal issues in relation

to unexamined social prescriptions marked a pivotal moment in my embrace of

adoption. I shall forever remain grateful to my friend for bringing me to the

place from which I could finally let go and move on.

A lecture engagement in January 1996 took me to

London and Paris. As I revisited familiar urban vistas, cafes, and boutiques

(irresistible as always), I imagined the pleasure I would derive from future

jaunts around town with my son and daughter. The sailboats at Luxembourg

Gardens, hot chocolate at Angelina's, the bird market, ice cream at Berthillon.

I tried to picture her as a teenager and as a young adult. Would she enjoy peering

into windows at Lolita Lempika's or casing the shops around the Place Victoire

as much as I do? The short months of pregnancy and newborn care seemed a tiny

fragment of the life I wanted to be part of.

Within days of returning home, however, my resolve

weakened inexplicably. My menstrual period threw me into a crisis of conviction.

I had not exhausted all of ART. Maybe if I did a Pergonal or Metrodin IUI cycle

with donor sperm, I could get pregnant. I called the clinic. Could I cycle?

Yes. I would need to come in early the next morning for a baseline ultrasound

of my ovaries, order the donor sperm and get the doctor's prescription for the

fertility drugs. Escape from controlling habits of mind was not as easy as I

had believed. As Michel Foucault had rightly observed, the body is the prisoner

of the soul. As soon as I put down the phone, I felt terrible. Traitor. I was

abandoning the baby whose quickening in my heart I had just recently begun to

feel more and more strongly. Should I really do this cycle? I vacillated. No,

I couldn't go through with it. But wait, the dossier had just gone off to Beijing;

it would take at least three months for the Chinese administration to act on

it. I could still play one path against the other. I woke the following morning,

put myself on automatic pilot and went to the clinic. Later that afternoon,

the nurse phoned to inform me that specimens from the donor I ordered were not

available. "Did we want to select another from the list?" Thank God, a sign!

"No," I answered, "It's too complicated, let's forget it." What relief I felt

as I hung up the phone. Peace at last?

Four weeks went by. At night I lay in bed imagining

the circumstances of my future daughter's birth and subsequent abandonment.

I knew that I would never have more than a general idea of the reasons leading

to her separation from her biological family and integration into ours. Family

planning policies in China and the culturally entrenched need for a male heir

created a devastating mix; was she a second- or third-born daughter? Or perhaps

the birth mother was unwed and had no means of supporting herself and a child?

How soon after the infant's birth would she be abandoned? How would it be done?

When would she be found? Would the birth parents leave a token or a note? How

long would it be before authorities in Beijing assigned us a child and grant

permission to complete the adoption in China?

Far more distressing questions haunted my sleep

and woke me before dawn. Would the birth mother make the decision and carry

it out herself, or would she be unduly pressured? Would her husband or mother-in-law

take the child from her by force? What if, on the contrary, she coldly turned

her back and walked away? (Let's not kid ourselves, this does happen and not

only in China.) I tried to enter the birth mother's state of mind. How could

I possibly fathom her feelings of grief and guilt? Would she suffer abiding

pain and bitterness? Would time bring healing and acceptance? Would she ever

know for certain whether her baby survived? Would she ever wonder about me?

World's apart, we would forever be unknowingly joined, by cruel and arbitrary

imperatives, in the life of a child whom she had conceived and I would raise.

ART, through its fertility drugs, had connected me to the bodies of anonymous

women across time, adoption, through its double bond of love and loss, across

space.

Then my period appeared, and I was again besieged

by the same gnawing doubts as four weeks before. Should I cycle? But what if

I actually did get pregnant? I wouldn't be able to go to China! And if I miscarried

again? I would lose everything. Despite the fact that I was on the verge of

not wanting anymore to become pregnant, I did make the early morning trip to

the clinic for the requisite baseline ultrasound. I got as far as the waiting

room and left. My heart was not there.... it belonged to a little girl who,

though I did not know it at the time, had in truth been born that very day.

I never returned to the clinic. I had enough of ART.

The planets had shifted their alignment in my

favor and a new, brighter star rose on the horizon. Spring had come to Washington.

As I walked back and forth between our home and the Friendship Heights Metro

station, I passed a large house on Western Avenue that had recently been sold

and spruced up. Plaques reading "Mother Theresa's Infant Home" and "Missionaries

of Charity" were posted on either side of the front door. Had a foundling hospital

been opened here? Curious, I decided to bring over the maternity clothes I had

been saving all these years but would now no longer be needing. A young Indian

nun, clad in the white cotton sari of the order, greeted me at the door and

invited me into the foyer as I explained my purpose.

"Could you, I mean your organization, use some

maternity clothes; they are in excellent condition?"

"Oh yes, we have someone here now," she replied.

I asked her about their mission in Chevy Chase D.C.

"This house is for pregnant girls, women, who

can't stay with their families, which are hostile to them, and so have nowhere

to go. We support them through the pregnancy."

"Do some choose to put their babies up for adoption?"

"All the babies are adopted through Catholic Charities,"

and she proceeded to enumerate the sectarian requirements for adoptive couples.

"But what happens if someone decides during the

course of pregnancy that she wants to keep her baby..."

"Well, then she has to leave."

"Pardon me?" Maybe I hadn't heard correctly...

"All the women who stay here have to put their

babies up for adoption."

Dumbfounded, I handed her the bag of clothes and

bid goodby. Quite a peculiar profession of charity, I thought; something seemed,

well, not quite kosher (or, as the French say, "pas très catholique").

Adoption through Catholic Charities is as expensive as through any other non-profit

venue; adoptive couples pay the birth mother's medical expenses, costs associated

with her pregnancy (like maternity clothes and counseling), agency social workers

for their home study, and all the legal fees involved. The overhead for the

one or two residents of the Chevy Chase "shelter" was for all intents and purposes

absorbed by adoptive couples. The women needing the most support were, presumably,

those who wanted to parent in the face of disapproving, angry families. I wondered

where they were supposed to go: return home? (The nun neglected to tell me,

I have since learned, that the Missionaries of Charity operate another house

in the District for women who do indeed choose to keep their babies. The two

groups of expectant mothers are therefore segregated, a policy that, it seems

reasonable to speculate, prevents the decisions of some from impinging on the

resolve of others.)

Where exactly did charity come into the picture?

In the ritual gesture I had just performed, of course. Did I do any differently

than the abbot of Cluny who once a year washed the feet of twelve paupers in

humble imitation of Christ serving the apostles? The religious orders distributed

food and clothing to the poor at funerals and anniversaries on behalf of deceased

benefactors; it was their job to convert the material wealth of rich donors

into heavenly treasure for the same. Money-laundering, medieval style. My modern

feminist re-staging of St. Martin, or St. Giles, or St. Francis clothing the

beggar - the archetypal demonstration of mercy in medieval hagiography

- had come right off the painted walls of the churches I studied. Ah, so that's

how images work.

Fig.

7.

Saint

Giles clothing a beggar, wall painting c. 1200, in the crypt of the Collegiate

Church of Saint-Aignan-sur-Cher.

Whether my maternity clothes provided needed assistance

to anyone is doubtful. The act of giving them away, however, had important symbolic

value. It represented a definitive break with my procreative body and put closure

on the reproductive phase of my life. (Similarly, in the saint's life, the gift

of a garment signifies more than an ascetic renunciation of worldly goods and

carnal pleasures; it epitomizes the shedding of high social rank and all fleshly

ties to kin, including the responsibility for dynastic propagation.) By the

end of June 1996, I had lost track of my menstrual cycle: I had forgotten the

date of my last period, and was surprised when it came. For the first time in

over three years, I was free.

1.

I owe the section heading to John Boswell, The Kindness of Strangers.

The Abandonment of Children in Western Europe from Late Antiquity to the Renaissance

(New York, 1988).

Genealogies

and Generations

Fig. 8. Lineage of Adam and Eve, miniature painted

by Stephanus Garsia Placidus, third-quarter of the eleventh century, Paris, Bibliotheque

Nationale, MS. lat 8878 (Beatus of St. Sever), fol. 5v. |

On

the sultry Monday morning of September 2nd, Armand and I look out

from our hotel window at the futuristic city-scape of Shanghai. We would soon

meet our daughter for the first time. According to official records, she was

found in a suburb far to the north of the city on March 6th ; a birth

date of March 3rd is presumed. Orphanage staff had named her Wang

(the patronym assigned to all their 1996 foundlings) Li Bei; her characters

literally mean "energy treasure." Since receiving our assignment some two weeks

before, I have been spinning a mental tapestry of prized and priceless qualities.

Sketchy outlines of a spirited temperament emerge in the foreground: dynamism,

vibrant power, vitality in vast abundance. I stare at a black and white image

of her in a photocopy of a fax transmission made from a photocopy of an undated

photograph. I try to glean the proverbial thousand words. A lifetime of deciphering

images has not equipped me to see through a glass this darkly. I think of Ira,

barely six, now with my parents in New York. He had understood. When I first

brought home the documents from the agency and showed Ira the picture of his

new sister, he kissed it. Still, I have no clue.

Everything has led up to this day, but when the

interpreter from the Shanghai Adoption Administration accompanies us to the

Children's Welfare Institute on Pu Yu Road I feel unprepared. Into the garden

courtyard, through the double doors of the building, up the stairs and down

the hall to a small living room where Armand and I, petrified with anxiety,

wait in silence. The director of the orphanage brings our six-month old baby

and places her in my arms. The moment for which I had ached is now. Language

ceases. My body takes over; it alone knows what to do. I am in the midst of

a purely physical event, like giving birth or being born. Gradually my mind

registers the sounds of applause and picture-taking. Armand holds the baby.

The director wants to know what we will call her. "Gabrielle Libei," I stammer.

"Gabrielle Libei Rose," Armand adds, "after my mother." Both our children now

bore Americanized forms of the Yiddish names of Armand's parents, survivors

of Auschwitz and Ravensbruck, who had passed away only shortly before Ira's

birth. The handing down of names from the dead to the living signaled the continuity

of the generations. As the director assumed custody of the baby for the last

time, we brought our visit to a close. The next morning we would begin finalizing

the adoption.

On the way back to our hotel, the interpreter

laid out the week's schedule. Was it 4:00 or 5:00 p.m. already? Armand and I

strolled along the Bund by the Huangpu River. Kites and balloons danced overhead,

loaded barges crept along. Behind us stood nineteenth-century buildings that

had belonged to the foreign concessions during the period of Western colonial

domination. Ahead in the distance, the Pudong TV and Radio Tower soared into

the sky to reclaim the city. Neither one of us could speak about our experience

at the orphanage. We were too stunned.

Less than twenty-four hours later we were playing

with the baby in the privacy of our hotel room. Gabrielle laughed a full belly

laugh that rolled over her plump little body and flooded mine. In that instant

of recognition, I became hers forever. Something in the ring of her laughter,

her sparkling eyes and the grasp of her tiny hand curled round my finger told

me that I had found all I had been searching for. She was my very own. Moment

by moment, day by day, physical intimacy sealed our deepening attachment. I

got to know my baby not in a hospital maternity ward but while exploring the

bustle of Shanghai and the gardens of Suzhou. Everywhere people responded to

her loveliness and congratulated us. I was especially moved by how much the

staff of the Shanghai Adoption Administration and Children's Welfare Institute

cared for her. They showered her with beautiful gifts - mementos of the city

(including a miniature crystal replica of the TV Tower), a childhood memory

album, a cup emblazoned with her baby picture. When finally we flew home, it

was Rosh HaShannah. Gabrielle lay sleeping against my chest, and sometimes suckled

the tip of my nose. I tasted the sweetness of the New Year. Such great good

fortune I had not imagined could be mine.

I watch my children grow, delighting in the person

each is. I thrill to both. To say more would be to trivialize the somatic intensity

of my passion for them. That passion springs not from conception and birthing,

nor from sharing a gene pool, but from the maternal relationship to which I

assent and which I renew every waking and sleeping minute until it is time for

my name to be passed on. The years I spent consumed with and by reproductive

technologies seem now strangely unreal. How could I have been so driven? To

what purpose? Yet, I wonder... Perhaps the experience of ART helped me to see

beyond nature. Needles, probes and monitors demystified procreation, revealing

it for the mechanics that it is. The real story lies in how humans translate

the single mode of generation common to the species, a biological phenomenon,

into the culturally diverse structures that make family a social artifact.

Fig.

5.

Vein/

Zodiac Man, miniature from the Wellcome Apocalypse, fol. 4 1 r.

|

|