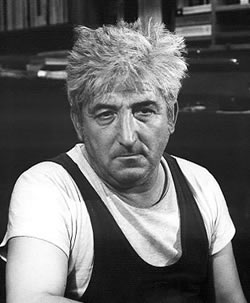

by Eddie Woods || Author's Links

Eddie

Woods interviewed Jack Micheline on December

7th 1982, three days after Jack's reading at Ins & Outs Press (subsequently

released as a spoken-word audio cassette entitled Jack Micheline in

Amsterdam). Jack had flown to Amsterdam, all expenses paid, to appear

at the annual One World Poetry Festival and was staying as Eddie's guest

in a top-floor apartment of the Ins & Outs building, next door to

a 17th-century church on the quiet fringe of the garishly bustling red-light

district. It was a busy and rewarding year for Jack: a few months earlier

he'd been voted 'most valuable poet' at a Kerouac festival sponsored by

Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, an event he was able to attend

only because enthusiastic friends in San Francisco had raised his bus

fare. He had also performed at the Poetry Olympics in London, before returning

to the States he enjoyed a highly--successful exhibition of his paintings

at an Amsterdam gallery.

Eddie

Woods interviewed Jack Micheline on December

7th 1982, three days after Jack's reading at Ins & Outs Press (subsequently

released as a spoken-word audio cassette entitled Jack Micheline in

Amsterdam). Jack had flown to Amsterdam, all expenses paid, to appear

at the annual One World Poetry Festival and was staying as Eddie's guest

in a top-floor apartment of the Ins & Outs building, next door to

a 17th-century church on the quiet fringe of the garishly bustling red-light

district. It was a busy and rewarding year for Jack: a few months earlier

he'd been voted 'most valuable poet' at a Kerouac festival sponsored by

Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, an event he was able to attend

only because enthusiastic friends in San Francisco had raised his bus

fare. He had also performed at the Poetry Olympics in London, before returning

to the States he enjoyed a highly--successful exhibition of his paintings

at an Amsterdam gallery.

Eddie and Jack met again in the Netherlands

10 years later, when they performed together at the 1992 North Sea Jazz

Festival. Although the two maintained a lively correspondence until shortly

before Jack's death in February 1998, this interview got misplaced in

the shuffle of vicissitudes and only recently resurfaced.

JM: I was fucked up like anyone

born in the Bronx, in an Irish-Italian neighborhood. You don't know who

you are and the first part of your life you open your eyes and you're

born, and everybody's running around throwing snowballs and water bags

on priests and punching each other out in the schools and you don't know

what the world's all about; and then you realize it's about struggle,

about trying to be yourself. And then you go through many avenues of struggle.

You join this and you join that and you find that whatever you join, they're

full of shit because it has nothing to do with you. So in the beginning

of your life you search. You search for what is good for you, and usually

what you do is go outside of yourself and find nothing. You have to search

inside, within your own being. So that's what happened. The first part

of my life I consider the search for one's self. The second part--and

I did become a poet--was being somebody who wrote down the vision and

the truth from the spirit that I'd tapped into. And the third part is,

after I'd tapped in, into all that spirit, I teach, I show the way. And

so this is maybe the sixth day of my third life.

EW: Here's to that good life. [Eddie raises a cognac snifter]

JM: Well, whatever it is, whatever that meshuggeneh life is.

EW: And how exactly did that come about, arriving at this enviable

point?

JM: Let me explain something. I never had a desire to be a poet. I

came from a very poor, tough section of the Bronx, and poets were sissies.

Who knows what a poet is? But when you come from the very bottom and you're

self-educated or streetwise, the word for a poet is, he's a fruit or a

sissy, whatever, a guy carrying a plow, with a long coat on. Who knows

what a sissy is? Hey, it's okay, Snuffie! [Eddie's canine companion, about

whom Jack later wrote, in a letter to Eddie: "Snuffie is not a dog!"]

EW: Keep talking, Jack, I'll get his bone.

JM: [Laughs, says "Yeah, okay."] That's the mentality of

a gangster. You see only what you see and you don't see beyond your nose.

Most people don't see beyond their noses; they are fucking followers,

they are not leaders. Most people are sheep. Most people...let's say,

for instance, many of the girls in Holland--not all, for sure, but in

my experience a lot--many are good-looking but when you start talking

to them, you find out there is nothing in their heads: their bodies are

luscious but there's nothing upstairs, they're zeros. But when you find

for yourself that you've got something in your head, you start searching

for more, because you've already begun tapping into something you never

had before. So already you're a winner. And the more you find, the more

you search for. So I tapped in.

I hit Boulder at the age of 52, right? Why

was I invited to Boulder? Because Jack Kerouac wrote the introduction

to my first book of poems [River of Red Wine, 1958]. And how was

I published? I walked in the rain one night and I knocked on a fucking

door that said Pocket Poets and a guy answered the door and he said he

publishes poets and I said I've fucked around for three years here and,

I don't know...could you look at a manuscript I have? He says bring it.

I went back, brought him the manuscript, and he says come back in a week.

Then he says, "On two conditions I will publish your book. You change

the shape of the poems and you get a famous man to write the introduction."

I said, "Haha, I don't know any famous people. Shit, I'm just a guy

that works in a sweater factory who writes poems."

EW: Pocket Poets. You mean Ferlinghetti?

JM: No, Ferlinghetti never published me. The guy [Malcolm Whyte] had

a sign, it was Troubadour Press out of San Francisco. He went to live

in New York, because his wife wanted to study with a ballet master. Ferlinghetti

has nothing to do with me.

EW: You said the other day that you're not a professional poet.

JM: Hell, no. I've never been a professional poet in my life. I live

it. I walk in the streets and I get the message and I write it down. What

professional poet? I never graduated high school.

EW: So what is a professional poet?

JM: All right, a professional poet is somebody who hustles and makes

a living from the shit, or who tries to make a living from it. And a living

poet is every minute you are a poet, you don't have to write to be a poet.

A shoemaker could be the greatest poet. The way he hammers the nail in

the fucking shoe is poetry. The way a woman lifts up her hair, lifts her

skirt, a hooker, the way she smiles, that's poetry. When it's a living

thing, it's poetry. But these people who are hung up on fucking words

and shit, the academic mentality, they're not poets. They're jerking off,

one hand against the other. So it isn't what you say, it's what you do

that makes you a poet.

EW: But aren't there some, what you would call professional poets,

who are also living poets?

JM: Right, sure, they study the poems, they read everybody else who

comes out. They read in the universities. They get the rich people to

back them or the big companies to publish them. But to me they are not

saying anything. So they might have good use of language, they may write

some interesting poems; but they are not moving it out to the masses,

they are not saying anything to the people who are dead, who are the living

dead. And the idea of a poet is to wake up the dead, shake up the ones

who cannot think, cannot smell, taste, feel or breathe. And so they are

not revolutionaries in the sense of trying to shake up the system. They

want a piece of the action and they want to be rich and famous and they

do not want to shake up anything. They are not revolutionaries. They are

not people who are willing to put their life on the line to change the

system or to make the world a better place for most people to live in.

In other words, they are doing it for the money.

EW: Okay. But I'm going to push you on this.

JM: Push as hard as you can.

EW: Are you saying that commercial or academic success is, of necessity,

incompatible with being a real poet? So I repeat: are there no, what you

call professional poets, who are nonetheless writing 'living poetry'?

JM: They breathe and they let live and they work hard and they are

craftsmen. They are good at their craft. But my poetry has nothing to

do with anyone else writing today. It has got to do with my vision, which

is very personal, very in tune with the whole universe, with what I consider

to be the universe. I don't write for other poets and I don't write to

be accepted by the academy. I don't even send my work to the academy.

EW: Right. What is for you the chief reward, or highest possible reward,

you can get from writing?

JM: All right, the other day [at the Ins & Outs reading] when

Santiago bought my book, turned to a poem and read it to the audience?

That poem had never before been read to any audience in the world. That's

one of the highest, when you can turn a stranger on to get up to the microphone

and dance. That is one of the high rewards.

EW: How about what the writing of a poem does for you?

JM: It's good when you write a poem you like. When I do a good painting,

I feel good, and it feels good when you write a good poem. That's the

reward in itself. What comes afterwards is something else.

EW: I'm talking about the act of writing...

JM: The act of creation...

EW: Yes, when you make a discovery.

JM: I walk out in the night and I take one step and then another,

right? Lorca spoke about duende, he talked about the spirit. He

made a speech at Havana University in 1929. A young student said, "Mr.

Lorca, could you tell us about the act of creation itself? What is the

spirit that moves you?" And Lorca replied, "I do not write my poems,

the spirit writes them for me. The duende writes the poems for me."

And this is what he later said: "Most of these guys, the duende doesn't

write for them. They're craftsmen. They know language, they know images.

But it isn't the spirit that moves them. Only the blessed ones, the great

ones, are blessed with this gift, to open themselves up and let the spirit

write." Is that an answer?

EW: Yes. You wrote somewhere, I forget if it was in a poem or an introduction,

something like "not for me the polished line or the line that's rewritten."

JM: I don't rewrite. Most of my work I do not rewrite; very rarely,

unless it's an obvious flaw or a bad line. But there are very few flaws

because I write from a high source. By the way, one time-this is very

interesting--Jimmy Baldwin introduced me to his publisher, Dial Press,

back in the sixties, '61 maybe. And he sent my second manuscript, called

Poet of the Streets, to Harvard University. And I happened to get

a copy of what the man said, the professor at Harvard who looked at the

manuscript. He said there were a bunch of images strung together, but

he didn't think it was poetry. Now the question is: Hey, Eddie Woods,

what is poetry? Can you tell me what poetry is?

EW: My own poetry, ideally, is a vehicle that takes me to a place

I've not yet been, allows me to discover new realms, that produces new

visions. Or as Bill Levy put it, when asked why he writes, "To get

what's heavy off the ground." As for the poetry of others, if it's

real, especially the truly great stuff, it also takes me somewhere...

JM: Where does it take you?

EW: That's unique for each poem. It can be a new viewing point, where

you see the familiar, the mundane, in an entirely different light, and

then get reminded of that when you read it again. Or it can do something

else.

JM: But that's a general answer. And if that professor thinks he knows

what poetry is, he's all wet.

EW: Poetry is not something you can think about in his terms.

JM: Or that you can analyze or try and judge. Either it's there or

it isn't, and time will decide that.

EW: Poetry is so rich, so varied. The analyzers will never grasp its

essence, or nail it down in neat little pigeon holes.

JM: I read "The Ballad of Reading Gaol" by Oscar Wilde.

If you know the lines, it is a ballad, it's that kind of poem. But he

wrote it from a high source, and that's what real poetry is.

EW: A very moving poem, for sure. Takes you straight to the core of

suffering. Then there's Robert Service, who mainly wrote ballads and said

of himself that he wasn't really a poet, he was a writer of verses. But

much of what he wrote--"The Spell of the Yukon," for example--is

to my mind real poetry. Ginsberg and Corso are both real poets, possibly

great poets. But their approaches are totally different. One might even

question whether some of Allen's longer works can be called poems, in

the sense of being clearly definable units, i.e. traditionally structured

poem-things. But who the hell cares? What he writes is poetry,

and that's what counts. Gregory, on the other hand, is more classical.

Him I see as the reincarnation of a much earlier Beat, namely Catullus.

But to go back for a minute to something

we discussed earlier. You've already said that you seldom rewrite and

why. But there are those who say one should never rewrite. That you should

pen everything spontaneously, put the words down as they come, and then

leave them alone. Do you go with that?

JM: Hey, man, there's no two people alike. Everyone is different.

I have what I consider is an affirmation. I use poetry as a crutch, as

a club, as a stepping stone, as a cane to keep on walking, to affirm my

life, my spirit. I use it to keep my spirit going. I don't go up to a

girl, "Hey, baby, dig this poem, I wanna get laid." A lot of

people use it: "Hey, dig me, I'm a poet" or "Dig me, I'm

an artist." The poem is me and I am the poem. There's no separation

between my life and my work, and that's important. There is no separation,

I am the poem. "Too many streets have taken me out of this world."

EW: Dylan Thomas lived poetry all his life, and was a great poet.

And he rewrote his poems over and over again, up to a hundred times for

one poem.

JM: He was a craftsman. God bless him, he had the strength and energy

to do it. I came out of the street, I wrote on the street. I wrote my

ballads, I never studied ballads. I learned to write the ballad by doing

it. My worst subject in school was English. But I'm a freak. I'm a freak

that comes out into poetry. It was a blessed event, it enriched my life.

I never dreamt I'd be a poet, let alone have the capacity to create poetry.

EW: When did you start writing?

JM: I wrote some short stories when I was a kid. My mother ripped

them up. She was jealous.

EW: Jealous?

JM: Well, she didn't want me to write. But anyway [laughs], I was

a good letter writer. When I was in the Army, I used to write her letters

all the time.

EW: Do you still like writing letters?

JM: My letters are very precious. People who get my letters hold on

to them forever. I don't write that many, but when I do write one it is

a wild experience to the eyes, the mind. The thoughts ramble, they go

up and down like waves of electric beams in the night.

EW: I once had an argument with Mel Clay, when he said--in some context

or another--that he didn't consider letter writing to have anything to

do with art. I said I think you're completely wrong, that for me letters,

and certainly for a writer, are simply another form of literary expression.

And sometimes a superior form.

JM: You know why? Because of your relaxed attitude. When you're doing

it, there's no pressure on you. So when you're loosened up...

EW: It's a one-to-one thing.

JM: Yeah, when you're loosened up, baby, when you're loose... Not

like if you're worried about what people are going to say when you're

giving a reading, did your hair look good and all. The politicians, you

know what they do, they look in a mirror, they keep combing their hair.

They wanna make sure they look nice for the people.

EW: Speaking of readings, I find that one of the drawbacks of giving

readings, doing performances, especially if you do it too often--and I've

seen this happen to a great many performing poets, who are good, who give

good performances, can attract the public--they get caught up in the trap

of knowing what pieces, what poems, consistently work best with an audience,

and doing those same poems every time, doing them to death. Or even worse,

allowing their new work to be influenced by what they feel an audience

wants, tailoring poems for their performance value.

JM: I am very lucky, you see. This is my first time in Amsterdam in

18 years. And I don't do readings that often. They paid my plane-fare

both ways. I could never afford to come here. God bless the poetry festival,

the One World Poetry Festival. They brought us, me, in contact with so

many young, beautiful people here. Wonderful town. I mean, it's narrow

like all towns. It has its cliques and groups. But there's a good spirit

here.

EW: Did you hear, or run into, any poets at the festival who you hadn't

known before, and then got off on?

JM: I got off on Yevtuschenko. Well, I didn't want to shock the gentleman.

I liked his mind and we talked a little while. But the guy I really got

turned on by was a slightly known German playwright named Peter Helly,

from Berlin. He had a good mind. We really rapped, had a good session

together. But this is the great thing about the poetry festival, that

it's brought people together who we haven't seen for years. Like Alex

Trocchi, who I hadn't seen. A lot of people. The Beard was done

by Robert Cordier [Paris-based Belgian actor, director, etc.]. They were

eating pussy on both sides of the aisle. [Laughs]

EW: You said the other day that when you go back to America your main

work has to do with the revolution.

JM: The Beat Generation isn't the revolution. Whatever the Beat Revolution

was, the coming up of people who were against the status quo, will always

be. But I'm saying there are a lot of poor, white writers in the western

states who are coming into maturity now and they have not found any major

publishing house for their work. And there might be eight or nine or ten

of them. I think the country is ready to have that poor, white revolution.

We've had the Black Revolution, the Greens, the Women's Revolution...every

revolution; but the poor, white writers never got their shot and now it's

their time. That's history. It'll happen.

EW: Where are they mostly?

JM: New Mexico. Kirk Robinson is one, and many others. Carl Weissner

[German translator of Bukowski, et al] has the books. They send him all

the poetry books. He knows more about American poetry, the good poetry,

than any person in the world. You can't see it while you live there. You

have to see it when you're outside.

EW: "Outside of the soup," is what you said at the reading.

But there are many writers, Americans included, who are more popular abroad

than they are at home.

JM: True, but they should try to get published in their own country.

Even though, and I know, it's almost impossible for a good writer to connect

with a decent publisher who also has distribution. It's all controlled

by three or four presses. Black Sparrow, City Lights... I mean, they publish

some good people. But this is a group of writers who are coming into maturity

now. You understand? They've been writing for 20 years. And most

publishers--small press, big press--aren't revolutionary, even though

Ferlinghetti himself had some limited success with Coney Island of

the Mind, which sold maybe a million copies, I think, for New Directions.

But they're not revolutionaries and they're not looking for revolutionaries

or visionaries. They're looking to live a nice safe life and go to the

bank every week.

EW: Well, the publishing industry as a whole is experiencing financial

difficulties right now. Many small houses are being bought up, there are

mergers...

JM: I'm talking about the fact that publishers are businessmen. They

publish poetry that they think will make money. They are not philanthropists.

They can't afford to be. So is poetry a business or a way of life? I'm

asking you, which is it?

EW: It's a way of life, of course.

JM: But if you're a publisher, it's a business.

EW: And? You can't publish people unless you survive as a business.

It all depends on how you run your business, what your priorities are;

and your morals, if you will. It's like saying money is evil, which it

is not. It can either be evil or good, according to how you use it. I'm

reminded of Ira Cohen saying to me once, that as soon as a contract comes

into play it means somebody's going to get ripped off. But I know from

my own experience, also as a publisher, that not having a contract can

be disastrous. What is a contract anyway, but an agreement to agree? In

case you might forget what was said, agreed to, you write it down. And

then you sign it. At the end of the day, if your intention is to rip someone

off, you'll do it anyway, with or without a contract.

JM: Okay, so you're a poet and you're a publisher. Why did you start

Ins & Outs Press?

EW: It's a long and rather convoluted story, Jack. The nutshell version

is that it started me. That was the magazine. Then later I resurrected

it, as a press…another issue of the mag, books, postcards, and very soon

a Jack Micheline cassette. With a contract!

JM: An agreement to agree.

EW: Yeah. And I continue because I like editing and can't resist doing

my bit to get certain good work out there. Like that.

JM: Let's get back to that question of what poetry's about.

EW: What it's about? Well...

JM: People, huh? It's about people?

EW: It's about people, it's about many things. It's about the human

heart, about aspirations, visions, imaginings; ideas even, but expressed

in a special way. Poetry covers the whole spectrum of human experience.

And it's about God, however you might define or conceive of that elusive

notion. Poetry is the spirit that moves taking concrete form, as a sequence

of finely tuned, exquisitely honed words. And as you were saying earlier,

when speaking of Lorca, real poets are vehicles who are open to that spirit.

JM: Why are so many poets the most boring people I've ever met?

EW: Hey, most people are boring and there are very few real carpenters.

JM: Or shoemakers. You know, I had a bowl of soup once in the winter

of 1949 in New York. It was a cold winter and this guy had a place called

Cosmos. One of those dumpy Greek restaurants on Hudson Street, between

12th and 13th. A little place. It was cabbage. I remember it was red cabbage

soup. And you know why it tasted so good? It was cold as hell outside.

It was the way the man placed that bowl down on the table, that made that

soup so fucking great.

EW: Right, poetry in motion. One reason why so many writers and so

many poets, so-called writers and poets, are so boring, is because of

universal literacy and compulsory education. Okay, maybe that's going

too far, I suppose it's good if everyone can at least read and write.

But this compulsive drive for higher education is very often misplaced.

Many people are better off learning a trade, working with their hands.

When I was traveling in Ceylon, in Sri Lanka, I was struck by how much

land was lying fallow, because no one wanted to farm it. Young men didn't

care to work the land, they felt it was beneath them. They'd gone to college,

studied to become lawyers, accountants, managers, but couldn't get jobs;

there were no jobs. So they hung out on street corners in Colombo, wearing

soiled white shirts and stained ties, crumpled suits, scruffy shoes, and

complained, bemoaning their fate. Meanwhile, a naturally rich and luscious

country which had long been self-supporting was now importing the most

basic crops. Ceylon was importing chili peppers from India, man! I mean,

I don't care to be a farmer or a laborer, but some people are better suited

to that. And someone has to do it. A failed bank manager might become

a great poet, but it ain't necessarily so.

JM: Songwriters communicate with more people than poets do, because

they are writing and singing what the masses want to hear or what they

really feel about. And poetry in a sense is too elitist. It's too fucking

cliquish, elitist, whatever. The politics in poetry is the same thing

as gangsters in the garment center, or anywhere else. A lot of poets don't

get published because they don't fight their way in. They don't know how

to fight their way in.

EW: Also fight their way into the heart of a reading. I've seen people

try to perform, or just read their poems, in front of an audience they

couldn't control, because they're not comfortable on stage or maybe they

don't read well, they can't recite, no matter how good or powerful their

poems are. And they expect someone else to do it for them, to control

that audience, to make people listen. But it doesn't work that way, not

in this day and age. Except at certain venues, staid poetry societies

perhaps.

JM: I like to communicate. Like one time in Bughouse Square in Chicago,

I was kicked out of this rooming house. It was in the late Fifties and

it was a warm summer night and I sat down under a tree and began reading

my poems. And within five minutes there was a group of working people

around me and someone took off their hat and asked someone else to pass

the hat. I raised 60 dollars from those people and that was from reciting

my poems about the city of Chicago. That was a high moment in my life,

that I could move these working people to dig into their pockets, because

I blessed them and they blessed me back with the cash.

EW: We have a street poet around here, Aldo Piromalli, an Italian

who reads his poems anywhere and everywhere. I've seen him in Vondel Park,

for instance, just walk over to a couple of people sitting on a bench

and start reading them a poem, because he felt he had something they needed

to hear. And before you know it, other people are stopping and in no time

flat he has an audience a dozen or so strong. He even does it at the Milky

Way, the multimedia center where you performed, at the festival, just

stop people in the corridors and start laying a poem on them. And they

love it.

JM: That's great. So he can relate. That's wonderful. Is there more

coffee?

EW: There's always more coffee. Here. Say, have you also had the experience

of writing something that you knew was so good, so meaningful, so perfect

in your own terms, that no matter what anyone else might ever think of

it, you're happy with it?

JM: Of course! Hey, if I never sent a poem out--and I very rarely

do, only when someone asks me and I like the people--I would still get

my payoff when I write a good poem. Now if it gets published, that's a

bonus. But most poets want to get published as much as they can. I look

at it as way of life. I paint for my child, my child feeling. My colors

are my child. The writing is my seriousness. If I didn't write poems,

I probably would have bought a machine gun and killed a lot of people

a long time ago. It saved my life, poetry, because where I came from was

a gangster mentality. My head was in a gangster mentality. And so when

I got out of a ditch, somewhere in Illinois, and started writing fragments,

just fragments in the beginning, it was a new life.

EW: You want sugar in your coffee or are you sweet enough?

JM: Put a little sugar in.

EW: You're a city boy from the Bronx, you've hung out in Chicago and

a bunch of other towns, and now you live in California.

JM: Berkeley, in the mellow land. The people there smile but their

smiles are not real. Those are fishy smiles, they're not genuine. It's

because of the weather they smile like that. It's a freaky smile. You

see, they are isolated out there. The Rocky Mountains split them from

the real people. So we live in the sunny land of fairies. It's called

Fairyland. Woody Allen says it's the land of fruits and nuts.

EW: Does he? When I was a kid in New York, we used to say that California

is the only place where fruits and nuts can grow together. Timothy Leary

wrote that the most intelligent people on the planet are in California.

And as you go eastward from there, he says, intelligence diminishes. Frankly,

I think he's nuts to say that. Where does that leave India, or Japan?

JM: Everyone has his own opinion. I think America is quite an interesting

country. It's a huge country and it has a lot of different forces at work.

You can't count it out. You bounce back. You come down and you spring

back up.

EW: Do you ever have problems in America with 'the movements'? You

know, the gay movement, Hispanics, the women's movement, concerning what

you can or ought not to say, or even what sort of ethnic or gender representation

you have at a performance event? You're familiar with the San Francisco

scene and I'm asking this particularly because, following an Ins &

Outs gala benefit two years ago in the Haight, at the Grand Piano, which

I flew out fo--really big do, it was--16 or so performers, Jack Hirschman,

Mel Clay, Roberto Valenza down from Seattle, many people...shortly afterward,

Steve Abbott, who was actually one of the organizers, wrote in Poetry

Flash-he's the editor, right?--that the ratios were biased or reflected

a bias. Like there were no Blacks--in the audience, yes, but not reading--and

too few women, et cetera. And I thought, 'come on, already!' I dig where

he's coming from, trying to keep everyone happy and all, but...

JM: If you think that way, you might as well put yourself in a shoe

box.

EW: But these pressures exist, especially in the States. And God help

you these days if you use the word "nigger" or "queer"

in a poem. Like, are they going to retitle Conrad's novel The Black

Man of the Narcissus or something?

JM: Okay, let's get to a more important point. Snuffie! Speech! You

do your thing, then I'll do mine. [Snuffie barks] Self-liberation, or

what I think self-liberation is. You go through all that shit when you're

younger, all these groups and causes...blacks, greens, blues, commies,

socialists, pinkos, right wingers, left wingers, bureaucrats, conservatives,

all this shit. It has nothing to do with liberating yourself. Liberating

yourself is you go beyond the politics of the narrow minds, the politics

of greed, the politics of power, and you walk on a cloud. 'What do you

mean,' you might ask, 'you walk on a fuckin' cloud? What are you, some

kind of saint or fairy or something?' You walk on a cloud, like a Chinaman...

I wrote a line, "Poetry is like a Chinaman walking in the sky."

[Laughs] Baby, if you took a walk like that Chinaman, you can keep walking,

out into the night. I assure you. When you go into San Francisco and you

have Hirschman with the Stalinists, Abbott, the politics of Poetry

Flash, Women's Liberation, Greens, Blues, whatever they've got, it's

bullshit. You know why? The sons of bitches, 99% of the world--and I'm

looking right into this machine you've got here [the tape recorder]--99%

of the world is enslaved.

I tell you, I tell you

all people are enslaved,

all people are nervous,

all people are ill at ease.

I tell you, I tell you

all people are enslaved.

I tell you, I tell you

all people are enslaved.

People are so nervous.

people are so ill at ease.

I tell you, I tell you

all people are enslaved.

Even me. I get scared. But I'm saying, this is what I see. This is one

of the first poems I wrote, that McCartney picked up, and it helped him

become a songwriter. So I'm some sort of a liberator. I may not be a great

poet, but sonofabitch I influence a lot of people. That's what I want

to be, I want to influence a generation to come. Like Henry Miller, The

Air-Conditioned Nightmare, turned on a generation. Wilhelm Reich,

Listen, Little Man, turned on a generation. Vachel Lindsay, one

poem he wrote changed peoples' lives. I want to be the type of person...that

some young kid from Davenport, Iowa...takes a trip to Chicago, it ain't

too far away...goes into a bookstore in Chicago and in a little fucking

store finds a little book and he finds one poem and that poem affects

his whole life. That's what it's about. You can be spaghetti, Ferlinghetti,

sell a million copies and don't influence anybody. Or it's about a girl,

putting a finger on her leg and maybe looking at a star, that's okay too.

I like to move into a different space, I like to move people out to a

better space. So that's what you call an idealist, a dreamer, some schmuck,

some madman, whatever. This is what I believe.

EW: You've expressed great affinity for Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. Or

at least for what he does. What is it about him that you find so compelling?

JM: I'm not a follower of his. I'll tell you the story. It was a party.

I had a Collected Poems published about six years ago. A girl in

orange came to the opening and our eyes met. Her name was--she had an

Indian name, it'll come to me, I can't think of it right now. She'd gone

to Poona, to the ashram. After two years, she got disillusioned. She was

broke. She left her husband and she went into the mountains, to a little

cabin, and she asked God what to do next. For two days nothing happened.

On the third day, before dawn broke, the Spirit said: "You go to

Arkansas and climb such-and-such mountain. And on this mountain there

is something, which you will see."

Somehow she made her way to Calcutta, where

she begged or borrowed the money from somebody, who knows?, to go back

to the States. And she went to Arkansas and climbed the mountain. Halfway

up the mountain there was a kind of valley, a split between two enormous

rocks; and in this valley lay a field of crystal, of semiprecious crystal

quartz. And this girl started the Boulder Gem Company, which makes necklaces

and other jewelry, and now grosses a million bucks a year. And she goes

all over the world, climbing mountains.

She left me a tape, a Rajneesh tape, What

Is Truth? And there's a story in it that has to do with: If you found

a purse full of money, what would you do? It's a rabbi asking and he put

a purse on the floor, three guys picked it up and gave three different

answers.

One guy said, "I would take it and

run away. Ah, it's mine, I got it! You think I'm a fool, to return it?"

The second guy said, "I'd give it back."

And the third guy said, "I don't know what state of mind I'd be in.

Blessed be he, if he tells me the right thing to do. But I cannot tell

you what I would do."

And the rabbi says to him, "You are

a true sage."

So when you have that much intelligence,

where you don't know if a day from now you will be a very different person,

and you let the good Lord, the guiding Spirit do it for you...hey! So

therefore the man, Rajneesh, is no doubt not only well-read but well-educated

and wise. I don't give a shit if he has a hundred Rolls Royces. Maybe

he needs them. But there's a man who has really got a mind, and I respect

that. Because he's giving people pearls of wisdom. He's not ripping them

off. If they are in a state of ecstasy, that's more than those people

working a nine-to-five job. So he's giving people something, I think.

EW: I heard an early tape of Rajneesh's, it may even be the same one,

also having to do with "What is truth?" And there's an anecdote

about a couple living in a house very near to a railway line. And every

time a train goes by, which is very often, the whole house shakes, it's

really terrible. But the couple don't want to move, they'd invested a

lot of money in the place. So the wife contacts an architectural consultancy

firm to see what, if anything, can be done. She makes an appointment for

the following afternoon, but neglects to tell her husband; maybe she thought

to surprise him. Anyway, the consultant comes over and the woman immediately

takes him to the master bedroom, because that's the room nearest to the

tracks, where you feel the house shaking the most.

"Just sit here on the bed," she

says, "there'll be a train coming along very soon. You won't see

it from the window, on account of the high, thick hedges, but you'll feel

it all right."

Then she looks at her watch and adds, "Actually,

it won't be here for another 10 minutes or so and I have some shopping

to do. So why don't you just sit here and wait and I'll be back shortly."

The woman goes out, the train still hasn't

come, and in the meantime, the husband comes home. Into the house, straight

to the bedroom, sees this strange man sitting on the bed and of course

asks, "Who are you? What are you doing here?"

The consultant looks at the husband and

says: "I know you're not going to believe this, but I'm waiting for

a train."

So yeah, what is truth? Speaking of the

Rajneesh's chariots, and I'm not sure how many he's up to now, here's

a ditty for you. I call it "Bhagwan Boogie," and it starts with

the epigraph, Jesus saves, Bhagwan spends:

Twenty Rolls Royces

Yet only one key

God as the Driver

Divine Comedy

Twenty Rolls Royces

All shiny and new

Each of them saying

"If only you knew..."

Twenty Rolls Royces

How simple and free

A fast ride to Heaven

For those who can see.

JM: That's a nice poem, I like it.

EW: Is happiness, or the concept of happiness, in any way an important

quality of feeling in your life?

JM: My life has been tragic, very tragic. Anyone born with any genius,

who sees a direct light to things, relates to very few people. Kline,

the painter, lived a tragic life, died at 52; James T. Farrell, Jack Kerouac,

Charlie Mingus...people who were close to me. Most of the people I've

known have not led happy lives. Why? Because they're out there, they're

out there trying to find new things and some people resent that. They're

explorers of the mind, explorers of the senses, always moving out into

new spaces, always looking for new mountains to climb. And when they fall

off the mountain, it'll take maybe a year to get back on the track of

climbing another mountain. So you are always retracing your steps. Come

falling down, getting up, taking a blow. No one wants to see a genius

live to be recognized because, you see, they shake up the dead. The ones

that are dead are those who put the geniuses into the fucking graveyards.

Very few geniuses survive. They usually die very young. I know this.

EW: Do you? Victor Hugo lived to 83 or something. Henry Miller went

west a year or so ago at what, 88, 89? Da Vinci nearly made 70, which

wasn't exactly young for his time. You mention James Farrell and he was

75, for chrissake! So c'mon.

JM: Okay, okay! I said "usually." And you know what I mean.

And I know the people who try to kill the geniuses. Because, my dear knowledgeable

friend, the Devil, he runs the wheel. He runs the fucking wheel. He's

got the guys working for him and he runs the wheel of the world. That's

not to say that everyone's got a little devil in them. Some have a little

angel. I always express this in my poems, from darkness to light, from

light to darkness. Like in my poem "Black Tar in the Night."

And always through my poems weaves in and out like the river, light against

darkness and darkness against the light. And baby, if you've got the light,

you are blessed. You are a shining light in the dark wastes of man, in

the cities of man, in the shit of man, and of wasted youth. The shit on

the radio, on TV, in newspapers...everywhere you go it's killing kids,

day in and day out, with shit. Somebody is running that wheel with shit

so they can pick their pockets, pick their minds. So if you've got your

own spirit, you are way ahead of most. You know that, it's basic.

Now we are into the basics. If you're talking

about many of these publishers even, you're talking about shit, you're

talking about garbage cans. They're in it for bread, without one inch

of spirit. All right, no sweat. That's their trip. Everyone's got their

own trip. I don't condemn them for it. But they don't sit at my table,

because I'm narrow-minded. I only want my friends. The ones who are searching

for truth, they sit at my table. I don't need to have a cat sitting at

my table who doesn't have any light. Let him go to the other tables and

bullshit the ones who already believe in the papers. The ones with the

spirit, they know without words. Hey, they know by looking at a cat if

he's got the juice. They don't need a poem. Don't show me your poem, show

me your eyes, give me your hand. Like Ira Cohen, let me shake your hand.

Put it there. You ever notice how Ira shakes your hand and looks you in

the eyes? He knows something, the crazy Jew knows something. It has nothing

to do with, "Hey, baby, look at my poem." It has to do with

life. You are the poem. You are the ball that bounces. You are the stars

that jump into the moon. You are the dog. The dog knows, Snuffie knows.

You've learned a lot from Snuffie, right?

EW: He's my guru.

JM: So tell me something about Snuffie.

EW: I could tell you a lot, Jack. Like how I inherited him from a

young French whore who died in mysterious circumstances. And how he's

clued me into many secrets, where the answers were right there in front

of me, but I couldn't see them until Snuffie pointed them out. But this

is your interview. So for now let it simply be known that since yesterday,

when we were leaving the Chinese restaurant and he heard you say you were

going to write a poem for him, he's grown bigger. Like he's really counting

on it, you know. [Eddie & Jack laugh, Snuffie barks] Someone once

asked Krishnamurti whether or not he was happy. To which K replied, "I

don't know, I've never thought about it."

JM: That's a good answer. I'm happy when I'm creating or when people

who I'm with are really and truly alive, who I can respect. Like that

German playwright, who I didn't know, not before he came up to my room

and we rapped. He asked why I'm always using Kerouac, always mentioning

the guy's name. He said, "You've got your own juice. No need to bring

Kerouac into it." And I liked that. It showed he had juice.

I talk about moments. What is this, the

moments? The only moments in life are when you can get above the normal

state that most everybody is in and really rise up and do it. Do a good

job, write a good poem, make a good painting. I paint a lot. I've done

a lot of fine paintings, I've written many fine poems. And when I'm doing

it, when I'm absorbed in the creative act, the very doing is the deed.

When you stick your cock in a woman's pussy, it's in there, it's doing

it. The moment it penetrates is similar to the moment when you're writing.

You're out there doing it. When you write, you must write with total involvement,

you must be utterly taken by the activity. Those moments are what you

live for. And if you have many such moments in life, then you are rich,

richer than most people. More than any of those greedy dudes with bags

full of hundred-dollar bills or thousand-dollar bills or millionaires

who can't even write their names properly, all they do is sign checks.

Because they haven't got the spirit or the light. They don't know what

the moment is. So they buy art all their lives and try in that way to

capture what the artist has created. But they'll never have it. Sad, these

guys. Thousands of millionaires who don't know about beauty, truth or

the moment.

[Sings]

And you can't put a moment in bottle

And you can't put a moment in a can

You gotta take a walk in the sunshine

And do the best you can.

That just came off the top of my head.

[Sings again]

Sunny Jim in the morning

Sunny Jim at night

Gonna walk my head off, mama,

Until I get it right.

Comin' home, oh I'm comin' home,

With that ole train at five o'clock,

Comin' home, comin' home,

Gonna sing that song, comin' home.

I'm sitting with Eddie Woods

Here in Amsterdam,

He's got a funny smile on his face.

A dog named Snuffie's in the back,

He's got a smile on his face.

Comin' home, comin' home,

Oh, baby, I'm comin' hoooooome.

The moment, we've gotta find out what the moment's about. And then we

got it, we got it. Maybe I'll have a purple shirt on in a year. And I'll

climb down from a mountain. Now this I doubt this, but...the purple people

walking all over America, competing with the orange people and the green

people and the black people and the blue people. Who knows? It's a great

time ahead. Your life is always exciting. Always new challenges, new mountains.

You never know what's going to happen. Good times are coming, America.

A lot of shit's gonna move off the fence. The time is now, the time is

ripe. Coming home, coming home, oh baby I'm coming hooooooome.....!

BROKEN NEWS || CRITIQUES & REVIEWS || CYBER BAG || EC CHAIR || FICCIONES || THE FOREIGN DESK

GALLERY || LETTERS || MANIFESTOS || POESY || SERIALS || STAGE & SCREEN || ZOUNDS

©1999-2002 Exquisite Corpse - If you experience difficulties with this site, please contact the webmistress.